Xavier Albán R.

Sept 24, 2017

"Acuñación de Prueba 1832" |

"Ecuadorian Trial Coin Dated 1832" | |

|

Todos conocemos la historia de cómo empezó a operar la casa de moneda del Ecuador, que a sus inicios se le dio la labor de desmonetizar parcialmente las piezas adulteradas o de mala ley, la mayoría de ellas reales acuñados en Popayán. Es de conocimiento común que en Quito la fabricación clandestina de monedas falsas de metales comunes o bajo contenido de plata fue generalizada en los primeros días de la República. Esta fabricación clandestina de monedas falsas proliferó entre 1828 y 1831; esta es la razón por la que una de las primeras tareas de la casa de moneda de Quito fue identificar las monedas de 1 real de Popayán que tenían poca o ninguna plata. Normalmente, su contenido de plata era inferior al treinta por ciento y la solución fue desmonetizar estas piezas estas piezas de finura baja contramarcándolas con las letras "Mo" (medio = la mitad), para reducir el valor facial a la mitad. |

Many know that when Ecuador's mint began to operate, it was given the task of revaluing or demonetizing base metal coins, most of them denominated in Reales and minted in Popayan, Colombia.

It is common knowledge that in Quito the clandestine manufacture of counterfeit coins of base metal or low silver content was widespread in the early days of the republic. This clandestine manufacture of spurious coins proliferated between 1828 and 1831; this being the reason one of the first tasks of the Quito mint was to identify the coins of 1 real of Popayan that had little or no silver. Typically their silver content was less than thirty percent and the solution effected was to countermark these low fineness coins with the letters "Mo" (medio = half), to reduce the face value by half. |

Real de Popayán desmonetizado a la mitad mediante la contramarca Mo en el anverso.

Real from Popayan revalued to half of face value with countermark Mo on the obverse.

|

También debemos considerar que la casa de moneda tuvo el trabajo de contramarcar la moneda Granadina con el monograma MDQ (moneda de Quito), la misma que se estableció con el decreto del 26 de diciembre de 1832 emitido por el General Flores, comenzando ese trabajo a inicios de 1833. Así mismo, sabemos que a más de ese arduo trabajo de desmonetizar las monedas popayenses, se trabajaba simultáneamente montando todo el equipamiento para poder iniciar la elaboración de las primeras monedas, la misma que estaría lista para empezar a mediados de 1832, realizando su primera acuñación de prueba el 30 de agosto de ese año (Ref. La Moneda Ecuatoriana a través de los Tiempos de Melvin Hoyos, segunda edición, pág. 79). Hasta aquí no existe nada nuevo, todo está perfectamente detallado en varias obras. Pero lo que aún no está claro, es cuál fue la denominación de las monedas de prueba que se realizaron en agosto de 1832, que a criterio de algunos investigadores dicha emisión tenía supuestamente impreso la fecha del año siguiente (1833); es decir, que de alguna manera los operarios, tallador que elaboró el cuño, el ensayador Guillermo Jameson y el Director de la casa de moneda, el Coronel Alberto Salazzá, adivinaron que el decreto que ordenaría el inicio de operaciones se emitiría al año siguiente de que ellos tuvieran listo la casa de amonedación. Todo esto a pesar de la presión que ellos tuvieron por montar las maquinarias de la casa de moneda lo más pronto posible, debido a la imperiosa necesidad de circulante que existía en el país. Ese panorama, en mi opinión, debió hacer todo lo contrario, el hacer suponer al personal de la casa de moneda, que el presidente Flores debía emitir con celeridad el decreto para que salieran a circular esas monedas el mismo año que se acuñaron, o sea 1832. Eso es lo que dictaba el sentido común, aunque en la práctica no ocurrió aquello, pues efectivamente dicho decreto salió al año siguiente, pero los miembros de la casa de moneda no tenían como saber que este demoraría en emitirse. Por otra parte, en la obra del Sr. Eliecer Enriquez, “Quito a través de los siglos”, hace referencia la hipótesis de que las monedas de pruebas acuñadas el 30 de agosto de 1832 fueron las pesetas, y que según Melvin Hoyos se fortalecería esta hipótesis por no existir reporte alguno sobre el inicio de la acuñación de las piezas de 2 reales de 1833, lo que haría presumir que fue debido a una acuñación de prueba. Esta hipótesis tiene mucho sentido, razón por lo que ha sido aceptada por todos al punto de que nadie objeta que los 2 reales fueron acuñados en agosto de 1832; pero el hecho de que no se hiciera un reporte de inicio de esas monedas, no quiere decir de que no pudiera existir otras razones, solo basta con recordar que la elaboración de las pesetas fue irregular y muy pobre en número de piezas y nunca se llegó a concluir, porque la máquina de acuñar sufrió daños, lo que hace que me cuestione si eso no es razón suficiente por la que no se emitió tal reporte? Además, Melvin Hoyos menciona en su obra “La moneda ecuatoriana a través de los Tiempos” segunda edición, en el literal 7 de la página 102, que el Sr. Salazzá envió un reporte al Ministerio de Hacienda, con fecha 13 de septiembre de 1833, informando de la imposibilidad de reparar el tornillo del Balancín de la máquina de acuñar, y que hasta esa fecha solo lograron producir 400 pesos en pesetas; es decir que solo acuñaron 1,600 piezas de 2 reales hasta el 13 de septiembre de 1833. Sin embargo, en el cuadro de producción que el Sr. Salazzá presentó al Ministerio de Hacienda en 1836, reporta una producción total de 5122 pesos en pesetas de 1833, o sea 20,488 piezas de 2 reales. Entonces, fácilmente podemos concluir que 18,888 pesetas debieron acuñarse después del 13 de septiembre de 1833 para completar la producción reportada por Salazzá, una vez que la reparación de la máquina de acuñar se concluyera. No cabe duda que es un gran misterio que los historiadores deberán seguir investigando, para descubrir cuando y como se acuñaron las piezas de 2 reales de 1833. Hasta ahora solo se ha podido plantear algunas conjeturas. En mi opinión particular, puedo decir que cuando se requiere sacar un numerario a circulación, para satisfacer una demanda urgente, la lógica dicta que se comience por las piezas que demanden una mayor necesidad, que normalmente son las monedas de menor denominación, pues es el circulante más solicitado en todas las transacciones. Así se demostró cuando confirmamos que las primeras piezas que la casa de moneda sacó a circulación fueron los medios reales, seguido al mes siguiente de las monedas de un real. Entonces, si por sentido común se sabía que denominación monetaria iba a tener una demanda inicial…. Entonces, ¿porque la casa de moneda decidiría hacer una acuñación de prueba, en agosto de 1832, de monedas de 2 reales? … ¿No sería ilógico esto? Como indiqué, el sentido común dictaba que deberían haber comenzado las pruebas con la moneda de mayor necesidad, que era el ½ real. De todas maneras, cualquiera que haya sido la denominación de las monedas de pruebas, para mi criterio, estas debieron haberlos impreso con la fecha de 1832, porque se realizaron en agosto de ese año, y con seguridad la casa de moneda no podía imaginar que la orden de emisión se realizaría al siguiente año. |

We must consider that the Quito mint also had the job of countermarking the coins from Cundinamarca (modern day Colombia) of correct fineness with the monogram MDQ (Moneda de Quito), which was established by the decree on December 26, 1832 issued by GeneralFlores. That work was begun in early 1833. Likewise, we know that in addition to that tedious work of reviewing the problematic issues of Popayan, they had to acquire and set up the equipment necessary to begin minting of the first coins. The machinery was ready by the middle of 1832, and the first coinage was struck on August 30 of that year (Ref. La Moneda Ecuatoriana a través de los Tiempos de Melvin Hoyos, segunda edición, pág. 79). So far there is nothing new; everything is perfectly detailed in several works. But what is still not known is the denomination of the trial coins that were made in August of 1832! In the opinion of some investigators this emission supposedly had been minted with the date of the following year (1833); that is to say, that somehow the operatives, the engraver who made the die, the assayer Guillermo Jameson and the Director of the mint, Colonel Alberto Salazza, divined that the decree ordering the start of operations would not be issued until the following year. All this in spite of the pressure they had to assemble the machinery of the mint as soon as possible, due to the pressing need for circulating coins in the country. This scenario would have us believe that the staff of the mint assumes that President Flores should issue the decree with speed so that those coins came out the same year they were coined, 1832. That is what common sense dictated, although in practice this did not happen, for indeed the decree did not come until the following year (1833), but the staff of the mint had no way of knowing that the authorization would be delayed almost a year. That scenario, in my opinion, had to do the opposite, to suggest to the staff of the mint, that President Flores should issue the decree quickly so that those coins would circulate the same year they were minted, that is 1832, this indicated the logic, although in practice that did not happen, because the decree came out the following year, but the staff of the mint did not know that the issuance of the order would be delayed for so long. On the other hand, the book by Eliecer Enriquez, "Quito a través de los siglos", makes reference to a hypothesis that the test coins minted on August 30, 1832 were the 2 reales; and Melvin Hoyos supports this hypothesis in the absence of any report of the starting date for the coinage of the 2 reales of 1833, which one could presume was a trial coinage. This hypothesis is very logical, which is why almost nobody rejects the idea that 2 reales were coined in August 1832; but the fact that there was no report of the start of these coins does not mean that there could not be other reasons. One must remember that the minting of the two reales denomination was irregular with few pieces minted. The scheduled quantity was never achieved because the coin press suffered damage. I believe this may have been the reason that no such report was issued. Moreover, Melvin Hoyos mentions in his second edition, in Item #7 on page 102, of his work "La moneda ecuatoriana a través de los Tiempos" that Colonel Salazzá sent a report to the Ministry of Finance, dated September 13, 1833, informing of the impossibility of repairing the screw of the press, (“el tornillo del Balancín de la máquina de acuñar”) and that until that date the mint had only managed to produce 400 pesos in two reales coins; that is to say, they only minted 1,600 pieces of 2 reales up to the 13 of September of 1833. However, in the production report that Colonel Salazzá presented to the Ministry of Finance in 1836, he reported a total production of 5122 pesos in pesetas dated 1833, or in other words, 20,488 pieces of 2 reales. Then we can easily conclude that 18,888 pesetas had to be minted after 13 September 1833 to complete the production reported by Salazzá, after the repair of the coin press was accomplished. It is a great mystery that historians must continue to investigate, to discover exactly when and how the pieces of 2 reales of 1833 were coined. Until now it is only been possible to raise some conjectures. In my personal opinion, I can say that when it is necessary to put coins into circulation to satisfy an urgent demand, logic dictates that you begin with the coins that are most needed, which are normally smaller fractional coins, since it is the most requested currency for the majority of transactions. This was demonstrated when we confirm that the first pieces that were put in circulation were the half real, and in the followed month the 1 real coins. So, if it was known what monetary denomination was going to have the highest initial demand, why would the mint decide to make a trial 2 Reales coin in August of 1832? This does not seem very logical. As I indicated above logic dictated that they should have begun trials with the most needed coin, which was the ½ real. Anyway, whatever the denomination of the trial coins, in my opinion, these should have been minted with the date of 1832, because they were made in August of that year, and surely the staff of the Quito mint could not imagine that the authorization would not be made until the following year. |

Moneda de 1/2 Real con fecha 1832 GJ registrada en la NGC con el código 2810734-005

½ Real with date 1832 GJ certificated in NGC cod. 2810734-005

|

Esta teoría se puede sustentar cuando fui visitado por un joven coleccionista que me mostró una pieza de ½ real de su colección, con un muy asentado desgaste, pero que con claridad se observaba la fecha de la moneda marcada con el año 1832, lo que llamó toda mi atención. Le dije que esta pieza era extremada rara, que tal vez podría tratarse del eslabón que pudiera definir el misterio de las piezas de prueba que se acuñaron en agosto de 1832. En mi opinión no cabía ninguna duda la fecha que se observaba en la moneda. Sin embargo, para poder confirmar esta observación, enviamos la moneda a una de las reconocidas certificadoras de monedas como la NGC. Lamentablemente dicha pieza no pudo ser calificada por su muy alto desgaste. Sin embargo, la certificadora registró esta pieza con fecha de 1832, y así quedó establecido en el registro 2810734-005 como ½ REAL 1832 GJ “NOT SUITABLE FOR CERTIFICATION” Vale la pena mencionar, que cuando las certificadoras no pueden confirmar la autenticidad de una moneda, la registran como “QUESTIONABLE AUTHENTICITY” como el caso 2813928-003; o “ALTERED DATE” si la fecha fue alterada, como el caso 3719808-007; o “INELIGIBLE TYPE” cuando no pueden identificar con certeza el tipo de moneda, como el caso 2795087-006 (moneda de 5 sucres 1944 con el resello de 75 años del BCE). Pero en el caso particular de esta moneda de ½ real, ninguno de esos calificativos fue considerado; no cuestionaron la autenticidad de la moneda ni tampoco que la fecha haya sido adulterada, o si la pieza fue imposible de identificar. Además de ese espécimen, yo conocía otro caso de una certificadora de monedas diferente, la ANACS que registró la existencia de otra pieza de ½ Real con el año repisado (1833/2 GJ) con codigo 4732077; es decir, un 3 repisado sobre un 2, la que fue puesta en subasta en la casa HERITAGE, en enero de 2013, la misma que describía como una pieza MoR, unlisted overdate. |

This theory was substantiated by a young collector who showed me a ½ real coin from his collection, which was extremely worn, but the 1832 date was clearly visible. I told him that this piece was extremely rare, that perhaps it could be the link that could define the mystery of the pieces of proof that were minted in August of 1832. In my opinion there was no doubt about the date that was observed on the coin. However, in order to confirm this observation, we sent the coin to one of the recognized coin certifiers, in this case NGC. Unfortunately this piece could not be certified because of its extremely poor condition. However, the certifier registered this piece dated 1832, and thus was established in registry 2810734-005 as ½ REAL 1832 GJ "NOT SUITABLE FOR CERTIFICATION" It is worth mentioning that when the certifiers cannot confirm the authenticity of a coin, they register it as "QUESTIONABLE AUTHENTICITY" as case 2813928-003; or "ALTERED DATE" if the date was altered, such as case 3719808-007; or "INELIGIBLE TYPE" when they cannot identify with certainty the type of coin, such as case 2795087-006 (coin of 5 sucres 1944 with the countermark for 75 years of the Ecuadorian Central Bank). But in the particular case of this coin of ½ real, none of those qualifiers was considered; they did not question the authenticity of the coin or that the date was altered, nor if the piece was unidentifiable.

In addition to that specimen, I knew of another case from a different third party grading service, ANACS that recorded the existence of another piece of ½ Real with overdate (1833/2) with number 4732077; that is, a 3 over 2, which was put up for auction by HERITAGE, in January 2013, described as a “MoR” (medio real), unlisted overdate. |

1/2 Real 1833/2 GJ certificada por ANACS 4732077 y subastada en Heritage ell 3/ene/2013

½ Real 1833/2 GJ certified by ANACS 4732077 and auctioned at HERITAGE on Jan 3, 2013

|

Estos dos ejemplares me hace meditar la posibilidad de que la emisión de prueba, realizada en agosto de 1832, pudiera haber sido la moneda de ½ real acuñada con la fecha de 1832, y no la moneda de 2 reales acuñada con fecha 1833 como muchos historiadores piensan, y que como dije anteriormente era ilógico comenzar las pruebas con la moneda de plata de más alta denominación, y peor aún con la fecha del siguiente año. De ser correcta mi hipótesis, deberían existir más piezas de ½ real de 1833 con fecha repisada y que podrían estar ahora en algunas colecciones, pasando desapercibido por sus dueños, porque se atribuía este error a la pobre calidad de los detalles de un punzón tan pequeño. Para confirmar aquello, realicé una inspección visual de algunas piezas de ½ real 1833, en la que logré observar un detalle importante en la impresión de algunas de estas monedas. |

These two examples make me ponder the possibility that the emission of trials, made in August 1832, could have been the coin of ½ real minted with the date of 1832, and not the 2 reales minted with date 1833 as many historians think. And, as I said earlier it would have been illogical to begin testing with the highest denomination silver coin, and even worse with the date of a year yet to come. If my hypothesis is correct, there should be more pieces of ½ real 1833 with overdate that could be in some collections, unnoticed by their owners, because this error was attributed to the poor quality of the details of a rather than a smaller punch. To confirm this, I made a visual inspection of some pieces of ½ real 1833, in which I was able to observe an important detail in the minting of some of these coins. |

Arriba: 3 monedas de 1/2 real con fechas impresas sin defecto, guardando proporcionalidad y alineación entre los 4 dígitos. Abajo: 3 monedas de 1/2 rel con fechas impresas donde el último o 2 últimos dígitos tienen defectos, inclusive el primero no guarda proporcionalidad ni alineación con los 2 primeros dígitos de la fecha.

Top: 3 coins ½ real with dates struck without defect, keeping proportionality and alignment between the 4 digits. Bottom: 3 coins ½ real with dates where the last or last 2 digits have defects, including the first does not keep proportionality or alignment with the first 2 digits of the date

|

Se observaba que la mayoría de las monedas de ½ real de 1833 tienen una impresión de fecha totalmente limpia, en la que se visualizaba muy bien los 4 dígitos, guardando una proporcionalidad y alineación entre ellas. Pero hay otras piezas en la que se observaba que la fecha no son limpias, siendo lo más raro que en esos casos la disformidad de la dígitos de la fecha se presentaba solo en el último o dos últimos números, y en unos pocos casos se visualizaba que además de la disformidad de los dígitos, estos eran de mayor tamaño y su ubicación no se alineaba con los 2 primeros, sino que estaban ubicados en una posición de escalera ascendente. |

It was observed that most of the ½ real coins of 1833 have a totally clear date, in which the 4 digits are quite clear, keeping a proportionality and alignment between the digits. But there are other pieces in which it was observed that the date are not clear, being the rarest thing that in those cases the distortion of the digits of the date appeared only in last or two last numbers, and in a few cases it was visualized larger digits and their location was not aligned with the first 2, they were located in an upward stair position. |

1/2 Real 1833 con disformidad en los dígitos de la fecha; se observa los 2 últimos dígitos (33) mas grande que los dos dígitos iniciales (18), además de una ubicación en escalonamiento acendente.

½ Real 1833 with warp in the digits of the date; the last 2 digits (33) are larger than the initial 2 digits (18), in addition to an ascending staggered location.

|

Todas las monedas de ½ real que tienen disformidad en la fecha, tienen una peculiaridad, y es que ninguna de ellas tienen un problema similar en los primeros dos dígitos del año. Esto es raro, porque siempre se atribuía esta anomalía a la calidad tan pobre que Orellana le dio a los cuños de esas piezas, pero nadie se ha cuestionado que en todas ellas solo se observa esta anomalía en los dígitos finales del año. Es decir, que debemos creer que en los varios cuños que se hicieron para la elaboración de estas piezas, solo tuvieron un mal acabado del tallado únicamente en esos dígitos. O en su defecto, que las piezas eran tan pequeñas que cuando se hacía la impresión de ellas en la máquina de acuñar, el error se presentaba exactamente en la misma posición de la moneda afectando solo esos dígitos. ¿Es eso lo que debemos creer que sucedió con esas monedas? Me resisto en creer aquello. Es muy inusual que solo se presente una disformidad en los últimos dígitos y hace que me plantee el siguiente cuestionamiento: ¿Porque se presenta esta disformidad solo en los últimos dígitos de la fecha? La única respuesta hipotética que encuentro es que esa disformidad no es producto a la calidad de la elaboración del cuño, o a un error en la calidad de impresión de las piezas cuando fueron elaboradas; me hace pensar en la posibilidad de que se traten de correcciones realizadas en los cuños, muy probablemente tallados en 1832 para empezar la producción que supuestamente debía comenzar a mediados de ese año, es lo que debieron suponer el personal de la casa de moneda, por la enorme urgencia de demanda de monedas que tenía el país, sumado a la presión que tenían ellos para tener instalado las máquinas lo antes posible. Pero como el decreto no llegó a firmarse sino hasta el siguiente año, es muy probable que fuera necesario corregir esos cuños para poder usarlos, obteniendo algunas piezas con esta peculiaridad. La poca producción de prueba que se realizó en agosto de 1832 debieron ser unas pocas piezas con la fecha del año 1832, las que pudieron o no haber salido a circulación. Solo se ha encontrado esta pieza de ½ real 1832 que consta en los registro de la NGC y que probablemente sea única. Debemos recordar, que cuando Flores dio la autorización para la implementación de la casa de moneda de Quito, fue necesario recurrir a la casa de moneda de Lima, en diciembre de 1831 para obtener toda la información posible, pues la tirante situación que había entre el Gobierno del Ecuador y la Nueva Granada no permitía conseguir el apoyo de las casas de Popayán y Bogotá. (“La Moneda Ecuatoriana a través de los tiempos”- segunda edición, pag. 74) Recordemos también que en Lima tenía por costumbre corregir los cuños para reusarlos en los años siguientes, esto lo observamos en las acuñaciones de la Casa de Lima del Cuartillo (KM#143.1) de 1830/28, 1831/0, 1834/3, 1836/5, 1839/8, 1842/32, 1843/32, 1845/36, como también los ½ reales (KM#144.1) de los años 1827/6, 1829/8, 1833/2, 1835/3, 1836/5, en los 2 reales (KM#95) de 1803/2, 1807/0, en los 8 reales de 1803/2, 1815/4 entre otros ejemplares. Así observamos que los cuños no solo eran corregidos el dígito final del año, sino que en muchas ocasiones se corregían hasta los 2 últimos dígitos. Si se buscó toda la información de cómo se trabajaba en la ceca de Lima, me hace pensar, si sería posible que la costumbre de corregir el cuño también fue transmitido entre esos conocimientos a la casa de moneda de Quito. Si es verdadera esta hipótesis explicaría porque existen cuños corregidos el último y 2 últimos dígitos, como observamos en algunos ejemplares. |

The ½ real coins that have a warp on the date have a peculiarity, and none of them have a similar problem in the first two digits of the year. This is rare, because this anomaly was always attributed to the poor quality that Orellana gave to the punches of those pieces, but nobody has questioned that this anomaly is only observed in the final digits of the year. That is to say, we must believe that in the various punches that were made for the elaboration of these pieces, they only had a bad finishing engraving only in those digits. Or failing that, the pieces were so small that when they were struck the error occurred exactly in the same position of the coin affecting only those digits. Is that what we should believe what happened with those coins? I resist that belief. It is very unusual that there is only a warp in the last digits and it makes me think about the following question: Why is this warp presented only in the last digits of the date? The only hypothetical answer I find is that this warp is not a product of the quality of the elaboration of the punch, nor of an error in the strike of the pieces when they were made; it makes me think about the possibility that they are corrections made in the dies, most probably engraved in 1832 to start the production that supposedly had to start in the middle of that year, is what the staff of the mint should have assumed, the enormous urgency of demand of coins that the country had, added to the pressure that they had to have the machines installed as soon as possible. But as the decree was not signed until the following year, it is very likely that it would be necessary to correct those dies to be able to use them, obtaining some pieces with this peculiarity.

The little test production that was made in August of 1832 must have been a few pieces with the date of the year 1832, which may or may not have been released. Only this piece of ½ real 1832 has been found in the records of the NGC and that it is probably unique.

We must remember that when President Flores gave the authorization for the implementation of the Quito Mint, it was necessary to obtain information from the Lima mint in December 1831, because the tense situation that existed between the Government of Ecuador and of New Granada (modern day Colombia) did not allow the support of the mints of Popayán and Bogotá (“La Moneda Ecuatoriana a través de los tiempos” - segunda edición, pag. 74). Remember also that in Lima it was customary to correct the dies to reuse them in the following years, this is observed in the mintings of the House of Lima del Cuartillo (KM # 143.1) of 1830/28, 1831/0, 1834/3, 1836/5, 1839/8, 1842/32, 1843/32, 1845/36, as well as the ½ reales (KM # 144.1) of the years 1827/6, 1829/8, 1833/2, 1835/3, 1836/5, in the 2 reales (KM # 95) of 1803/2, 1807/0, in the 8 reales of 1803/2, 1815/4 among other copies. Thus we observed that the dies were not only corrected the final digit of the year, otherwise in many cases corrected to the last 2 digits. If they looked for all the information on how things worked in the Lima mint, it makes me think, if it were possible that the custom of correcting the dies was also transmitted to the Quito mint. If this hypothesis is true, it would explain why there are corrected dies in the last 2 last digits, as we observed in some specimens. |

|

El misterio del 2 reales 1833 Melvin Hoyos podría tener razón, al aseverar que la casa de moneda empezó a producir el numerario ecuatoriano a finales de diciembre de 1832, y que la producción debió comenzar con las monedas de ½ Real con el error de la denominación en quebrado realizados por Juan Orellana como tallador mayor. También debemos mencionar que el Sr. Juan Orellana fue el primer tallador mayor de la casa de amonedación desde 1832 hasta marzo de 1833 en que fue reemplazado por Eduardo Coronel. El Sr. Orellana fue el encargado de hacer las primeras emisiones de plata de ½, 1 y 2 reales. |

The mystery of 2 reales 1833 Melvin Hoyos could be right, stating that the mint started producing the Ecuadorian coinage at the end of December 1832, and that the production should have started with the ½ Real coins with the error of the denomination in fraction made by Juan Orellana as a major engraver. We must also mention that Mr. Juan Orellana was the first major engraver in the Quito mint from 1832 to March 1833 when he was replaced by Eduardo Coronel. Mr. Orellana was in charge of making the first silver issues of ½, 1 and 2 reales. |

Primeras monedas de ½, 1 y 2 reales acuñadas en la casa de moneda, atribuidas al tallador Juan Orellana. Se puede observar las características principales que las atribuyen a él, como el trabajo rústico de las piezas, la posición de las aves, el traslape de las montañas que forma el valle en V, el dentado de las gráfilas que son detalles inconfundibles, entre otras.

First coins of ½, 1 and 2 reales minted in the mint, attributed to the carver Juan Orellana. Can see the main characteristics that attribute them to him, such as the rustic work of the pieces, the position of the birds, the overlap of the mountains that form the valley in V, the teeth of the ring that are unmistakable details, among others.

|

Además, sugieren algunos historiadores que la pieza de 2 reales también pudo haber empezado su acuñación en 1832, al menos las 1600 piezas que Salazzá confirmó su producción en el reporte de 13 de septiembre de 1833 al Ministerio de Haciendas, informando de la imposibilidad de reparar el tornillo del balancín. Pero a mi criterio, de ninguna manera esas pesetas pudieron ser las monedas de pruebas, realizadas en agosto de 1832, porque cualquier moneda que se hubieran hecho en esa fecha, debió tener impreso el año en que se hizo la prueba, y no el año siguiente. No está claro si las piezas de 2 reales empezaron a acuñarse en 1832 o a inicios de 1833, lo que sí puedo decir con toda seguridad es que está pieza, a pesar de la poca producción, fueron trabajadas por ambos talladores, Juan Orellana y Eduardo Coronel, contrariando lo que piensan muchos historiadores que atribuyen la producción de las pesetas de 1833 solo al Sr. Orellana, porque consideran a estas piezas como la emisión de prueba realizadas en agosto de 1832. Para comprobar lo mencionado, podemos confirmar que existen monedas de 2 reales 1833 con los acabados característicos propios de cada uno de los talladores. Así lo confirmamos con las monedas certificadas NGC 4327326-009 que tiene todas las características que pueden atribuirse al Sr. Juan Orellana, y el número de registro NGC 3419565-008 que tiene las características inconfundibles atribuibles al Sr. Eduardo Coronel. |

In addition, some historians suggest that the piece of 2 reales could also have begun its coinage in 1832, at least the 1,600 pieces that Salazzá confirmed its production in the report of September 13, 1833 to the Ministry of Finance, reporting the impossibility of repairing the screw. But in my opinion, in no way could those 2 real coins be the trial coins, made in August 1832, because any coins that had been made on that date, should have shown the year in which the test was done, and not the year following. It is not clear if the coins of 2 reales began to be minted in 1832 or early 1833, what I can say with complete certainty is that this denomination, despite the low production, was worked by both engravers, Juan Orellana and Eduardo Coronel, contrary to what many historians think that they attribute the production of the pesetas of 1833 only to Mr. Orellana, because they consider these pieces as the emission of evidence made in August 1832. To verify the aforementioned, we can confirm that there are coins of 2 reales 1833 with the finished characteristic of each of the engravers. This is confirmed by the certified coins NGC 4327326-009 which has all the characteristics that can be attributed to Mr. Juan Orellana, and the registration number NGC 3419565-008 that has the unmistakable characteristics attributable to Mr. Eduardo Coronel. |

NGC 4327326-009 NGC 3419565-008

Juan Orellana engraver Eduardo Coronel engraver

| Podemos observar las características que identifica al tallador que realizó el cuño de cada pieza de 2 Reales 1833 que se muestran en las fotos de arriba: | We can observe the characteristics that identifies the carver who made the stamp of each piece of 2 Reales 1833 that are shown in the photos above: |

Monedas de 2 reales con las características atribuidas a los talladores:

Juan Orellana (izq.) acuñada probablemente en 1832 o inicios de 1833, y Eduardo Coronel (derecha) acuñada probablemente después de sept. 13 de 1833

Coins of 2 reales with the characteristics attributed to the carvers:

Juan Orellana (left) probably minted in 1832 or early 1833, and Eduardo Coronel (right) probably minted after Sept. 13 of 1833.

|

- Observamos que para el caso del cuño tallado por Juan Orellana, los acabados son rústicos y de menor calidad que el tallado del cuño de Eduardo Coronel. - La posición de las aves ubicadas sobre las montañas son totalmente distinta entre ambos talladores. Siendo esta la característica más relevante para determinar a quién corresponde cada cuño. - La formación del valle entre las montañas, que para el caso del cuño tallado por Orellana, el traslape de las montañas establece un punto de encuentro (vértice), dando la forma al valle en V; a diferencia del cuño de Coronel que se forma cuando el encuentro de la montaña de la derecha hace una curva cerrada para montarse sobre la falda de la montaña de la izquierda, formando el valle en U. - El acabado de las laderas de las montañas son muy diferente, notándose el fino labrado en la moneda proveniente del cuño de Coronel. - El rustico diseño del dentado de las gráfilas en la moneda de Orellana, a diferencia del muy buen acabado que tiene en la pieza de Coronel. - El acabado de los números que conforma el año 1833, en la que es muy notorio la diferencia de la forma de los dígitos, sobre todo podemos observar lo muy diferente que es el número 8 entre ambos talladores. - Y por último el detalle en la parte inferior de la cornucopia, que para el caso del cuño de Orellana es grueso y muy rústico, mientras en el cuño de Coronel los acabados son finos. |

- We note that for the case of the die engraved by Juan Orellana, the finishes are rustic and of lower quality than the carving of Eduardo Coronel's die. - The position of the birds located on the mountains are totally different between both engravers. This being the most relevant feature to determine which corresponds to each die. - The formation of the valley between the mountains, that for the case of the cut engraved by Orellana, the overlap of the mountains establishes a meeting point (vertex), giving the form to the valley in V; unlike the Coronel die that is formed when the meeting of the mountain on the right makes a sharp curve to be mounted on the skirt of the mountain on the left, forming the valley in U. - The finish of the slopes of the mountains are very different, noticing the fine engraving in the coin from the stamp of Coronel. - The rustic design of the teeth of ring in the coin of Orellana, unlike the very good finish that is in the piece of Coronel. - The finishing of the numbers that make up the year 1833, in which the difference in the shape of the digits is very no ticeable, above all we can see how very different the number 8 is between both engravers. - And finally the detail in the lower part of the cornucopia, which for the case of the Orellana die is thick and very rustic, while in the Coronel die the finishes are fine. |

|

Todas estas características identifican el trabajo de cada uno de los talladores, plasmados en las piezas de 2 reales 1833, lo que demuestra que a pesar de las pocas pesetas que se acuñaron de ese año, se hicieron en diferentes periodos y con ambos talladores, contradiciendo lo que hasta ahora se piensa, que todas las pesetas se realizaron en 1832 por Juan Orellana. Además, de lo mencionado hasta ahora, nos permite deducir que la moneda de 2 Reales acuñada por Juan Orellana, debería ser mucho más rara que la moneda de 1 real de 1833 tallada también por él. Solo he conocido el espécimen que consta en la foto de este artículo, tampoco ha sido reportado en las obras de Melvin Hoyos y Ramiro Reyes, en las que aparecen en ambas obras solo la moneda del tipo que corresponde al tallado de Eduardo Coronel, atribuyéndolas de manera errónea a Juan Orellana. Debemos recordar que, de las 20,488 piezas que Salazzá reporta en el informe de 1836 como producción total de pesetas, solo 1,600 se acuñaron en monedas de 2 reales hasta el 13 de septiembre de 1833 según lo reportado por el mismo Salazzá, cuando informó la imposibilidad de conseguir el tornillo del balancín; lo que quiere decir que las 1,600 pesetas que se produjeron hasta antes del 13 de septiembre debieron ser realizadas por el Sr. Orellana, que es menos del 8% de la producción total. Esta última afirmación se basa porque la orden de producir monedas de 1 real que recibió la casa de moneda, el 28 de Febrero de 1833, el art1 menciona: “Desde esta fecha se sellarán en la casa de moneda del Estado, reales de plata con el mismo tipo que las pesetas, a excepción que en el lugar donde se estampa el No. 2 se sustituirá por el No. 1” – “La Moneda Ecuatoriana a través de los tiempos” segunda edición de Melvin Hoyos, pag. 103; lo que deja claro que para cuando se dio la orden de acuñar la moneda de 1 real en febrero de 1833, ya existían las monedas de 2 Reales, y para esa fecha, solo podían provenir del cuño tallado por Juan Orellana, quien era el Tallador mayor de la Casa de moneda.

La producción restante de 18,888 pesetas (más del 92% de la producción total), con toda seguridad, debieron acuñarse después de la fecha del informe del 13 de septiembre de 1833, lo que quiere decir que solo podía ser realizado por el Sr. Eduardo Coronel que para entonces ya era el Tallador mayor de la casa de moneda. |

All of these characteristics identify the work of each of engraver enshrined in the coins of 2 reales of 1833 despite the few coins of 2 reales minted in this year they were made in different periods and contradicting what we have believed, that all coins of 2 reales were made in 1832 by Juan Orellana. In addition, from the aforementioned, it allows us to deduce that the coin of 2 reales coined by Juan Orellana, should be much rarer than the 1 real coin of 1833 also engraved by him. I have only known the specimen that appears in the photo of this article, it has not been reported in the works of Melvin Hoyos and Ramiro Reyes, in which only the coin corresponding to the carving of Eduardo Coronel appears in both works, attributing them erroneously to Juan Orellana. We must remember that, of the 20,488 pieces that Salazzá reported in the 1836 report as total production of pesetas, only 1,600 were struck in coins of 2 reales until September 13, 1833 as reported by Salazzá, when he reports the impossibility of getting the screw; which means that the 1,600 pesetas that were produced before September 13 must have been carried out by Orellana, which is less than 8% of total production. This last statement is based on the order to produce coins of 1 real that was received by the mint, on February 28, 1833; article 1 mentions: "From this date will be struck in the mint, 1 real coins of the same type as the pesetas (“pesetas” in Ecuador was synonymous with “2 reales”), except that in the place where the numeral 2 is stamped, it will be replaced by the numeral 1" – “La Moneda Ecuatoriana a través de los tiempos” second edition of Melvin Hoyos, pag. 103; which confirms that by the time the order was given to mint the coin of 1 real, in February of 1833, the coins of 2 reales already existed, and for that time, they could only come from the die engraved by Juan Orellana, who was the engraver of the Quito mint. The remaining production of 18,888 pesetas (more than 92% of total production), surely, had to be coined after the date of the report of September 13, 1833; which means that it could only be made by Eduardo Coronel, who by then was already the engraver of the Quito Mint. |

|

Conclusiones Como conclusiones podemos resumir todo lo mencionado hasta ahora en 7 puntos esenciales:

|

Conclusions As conclusions we can summarize everything mentioned so far in 7 essential points:

|

Xavier Albán R. - Junio 12, 2017

| "Un Inusual Repisado" | "An Improbable Overdate" | |

| Si bien es cierto que la historia numismática ecuatoriana es corta, debido a que este comienza su propia acuñación monetaria desde el año 1833, sí cuenta con una extraordinaria variedad de piezas que la hace muy rica e interesante para los coleccionistas.

Es común encontrar dentro de un mismo año, algunas diferencias muy evidentes que hace a cada moneda especial; variedades como cambios sutiles en los diseños del escudo, errores en el texto del Listel como letras invertidas o cambiadas, acuñaciones crudas, piezas repisadas, errores de acuñación, etc. Entre las variedades de monedas repisadas, existe una gran gama de piezas con fechas repisadas que enriquece nuestro numerario. Podemos observar que, con muy escasas excepciones, la mayoría de monedas con fechas repisadas se producen en las piezas de ½, 1 y 2 décimos, que van desde los años 1891 a 1912. Es muy enigmático que la mayoría de estas monedas se produjeron solo sobre estas denominaciones, y más enigmático aún es que casi todas ellas corresponden únicamente a la ceca de Lima. Las fechas repisadas no ocurren en las cecas de Birmingham y Philadelphia, y en el caso de la ceca de Santiago de Chile, Krause World Coin reporta el repisado solo de la moneda de UN DECIMO 1889/789, que por tratarse del 8 sobre 7 en la centena de la fecha, es evidente que se trata de una corrección de error de fecha. La pieza repisada de Santiago de Chile es muy poco común, y en el Censo de la NGC reporta la existencia de una pieza solamente. |

Whilst Ecuadorian numismatic history is short, due to its having begun its own coinage only in 1833, it does have an extraordinary variety of specimens that makes it very rich and interesting for collectors.

It is common to find within a single year some very apparent differences which make each coin individual, varieties such as subtle changes in the design of the shield, errors in the legend such as inverted or altered letters, crude minting, overstrikes, minting errors etc. Amongst the varieties of overstruck coins there exists a huge range of pieces with overstruck dates which enriches our coinage. We may note that with very few exceptions most of the coins with overstruck dates are found on ½, 1 and 2 decimos pieces from 1891 to 1912. It is very puzzling that most of these coins appear only in these denominations, and even more puzzling that almost all of them relate solely to the mint of Lima. The overstruck dates do not occur in the mints of Birmingham or Philadelphia, and in the case of the mint of Santiago de Chile, Krause World Coins records an overdate only on the ONE DECIMO coin 1889/1789, which, since it relates to an 8 over 7 in the hundreds of the date, is clearly dealing with the correction of a date error. The overdated piece of Santiago de Chile is very scarce, and the NGC Census reports the existence of only one piece. |

Único décimo de Santiago de Chile 1889/789 reportada en el Censo de la NGC

The only Santiago de Chile decimo reported in the NGC Census.

|

Vale la pena mencionar, que tampoco existe registro alguno sobre la razón de porque ocurrió estos repisados en la Ceca de Lima, pero esto había sido práctica habitual en las monedas peruanas desde inicios de esa República. Se piensa que el motivo de esta práctica era para optimizar los costos de producción de los troqueles. Se hacían varios cuños para ir reusándolos en los siguientes años, por lo que era necesario corregir los dígitos de la fecha con el año en que el Ecuador solicitaba un nuevo suministro de monedas. Esta teoría es solo una hipótesis no confirmada, pues como mencioné, no existe ningún tipo de registro que aclarare este misterio, que fue muy común en la ceca de Lima, y no se encuentra otra explicación lógica que permita una segunda hipótesis. De esa manera, investigando un poco los catálogos, encontramos las siguientes producciones que fueron repisados las fechas para su uso en años siguientes:

También existen algunas piezas de ½ décimo acuñadas en la ceca de Lima, con fechas repisadas que muestran la práctica de preparar troqueles con la última o dos últimas cifras de las fechas dejadas en blanco, pero que a pesar de ello debían ser repisados por el cambio de década o siglo, de esos casos tenemos:

|

It is worth mentioning that there exists no record of why these overdates occurred in the Lima Mint, but it had been standard practice on Peruvian coins since the earliest days of the Republic. It is believed that the motive was to optimize the cost of production of the dies. It is thought that the operating cost was less if larger quantities of dies were produced, so that the excess could be used in subsequent years, for which it was necessary only to correct the digits of the date with the year in which Ecuador requested a new supply of coinage. This theory is only a hypothesis of various experienced collectors, because as already mentioned there exists no kind of record which clarifies this mystery, which was very common in the Lima mint, and there is no other logical explanation which allows a second hypothesis. In this way, by checking the catalogues, we find the following coins where the dates were overstruck for use in subsequent years:

There also exist some ½ decimo coins minted in Lima with overstruck dates which show the practice of preparing dies with the last one or two figures of the date left blank, but which still needed to be overstruck because of the change of decade or century, such as:

|

Moneda poco común de ½ décimo 1899/87 JF con corrección de repisado en la decena de la fecha.

Solo existe una pieza reportado en el CENSO de la NGC

Scarce ½ decimo 1899/87 JF with correction by decade overdate. Only one piece is recorded in the NGC CENSUS

|

Esta práctica de repisar la década y/o el siglo en los troqueles, donde el dígito o los dígitos finales fueron dejados en blanco, era práctica común en la Ceca de Lima, esto se evidencia por la existencia en la serie peruana de ½ dinero 1900/890, 1901/801, 1901/891 , 1902/802, 1902/892, 1903/803, 1903/893, 1904/894, 1905/805, como también en 1 dinero 1900/890, 1902/892, 1903/893, y en el sol. 1890/80, 1891/81, 1892 / 82 y muchas otras piezas. Debemos mencionar que no existen registrados en los Censos de la NGC y PCGS, algunas monedas como los ½ décimo 1902/892 y de 1905/2, por lo que no se tiene confirmación de la existencia de estas piezas, sin embargo, ambas monedas están reportadas en el catálogo de Krause World Coins. Además de las monedas con fecha repisada de la familia de los décimos, existen otras piezas conocidas con este mismo error, y que corresponden a las monedas pre-decimal, entre las que existen reportadas las siguientes: |

That this practice of overstriking the decade and century on dies where the final digit or digits were left blank was common practice in the Lima mint is evidenced by the existence in the Peruvian series of ½ dinero 1900/890, 1901/801, 1901/891, 1902/802, 1902/892, 1903/803, 1903/893, 1904/894, 1905/805, 1 dinero 1900/890, 1902/892, 1903/893, sol 1890/80, 1891/81, 1892/82 and many more. We should mention that there is no record in the NGC and PGC Censuses of certain coins such as the ½ decimo 1902/892 and 1905/2, so there is no confirmation of the existence of these pieces, although both coins are reported in the Krause World Coins Catalog. In addition to the overdated decimal coins, there exist other pieces known with the same type of error corresponding to the pre-decimal coinage, amongst which the following are recorded: |

|

|

|

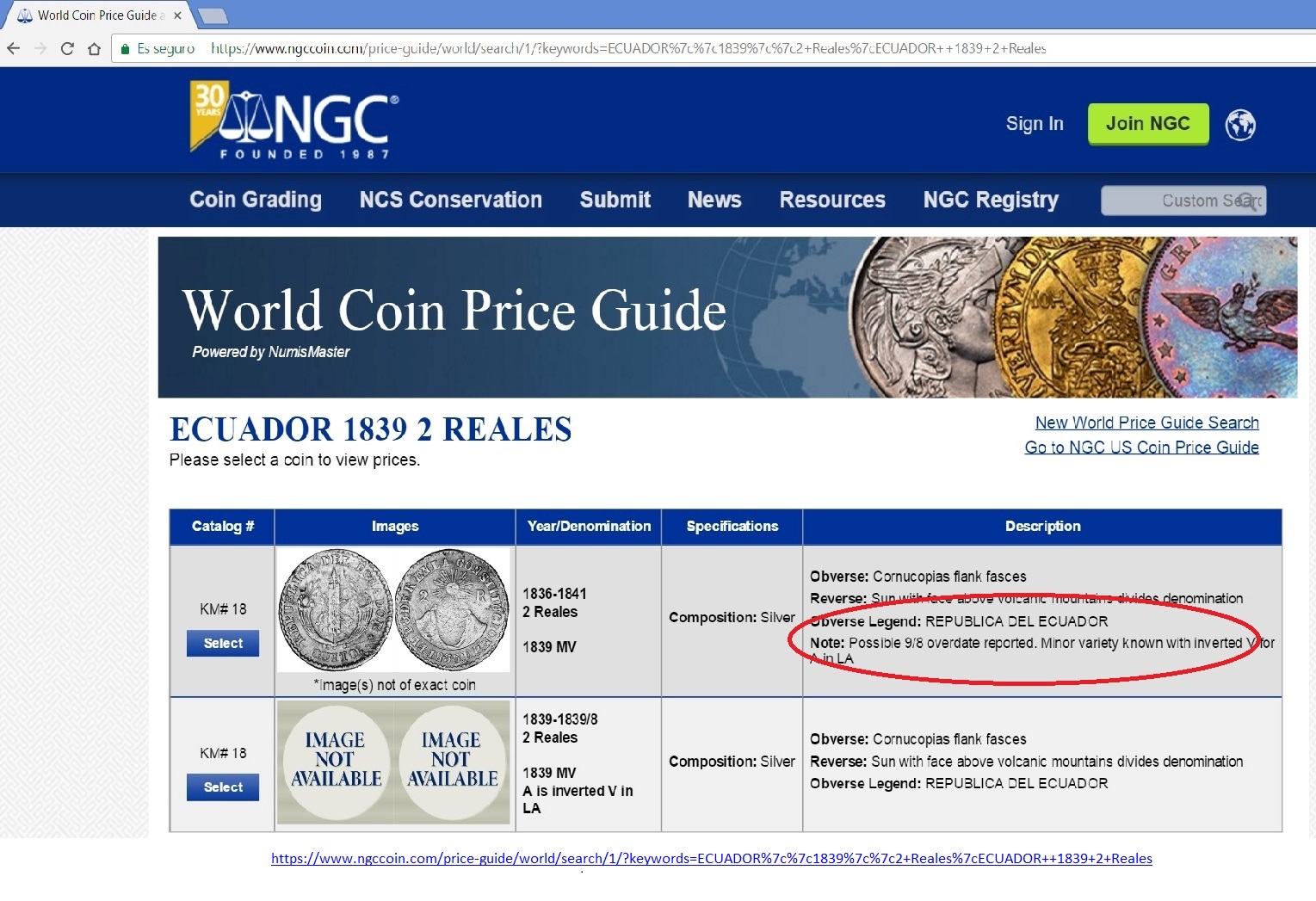

Todas estas piezas repisadas pre-decimal, están confirmadas su existencia. También NGC menciona la posible existencia de una pieza repisada de 2 Reales 1839/8 MV, sin embargo aún no existe reporte alguno en el Censo, razón por lo que no podemos confirmar su existencia. |

All these pre-decimal overstruck pieces are confirmed to exist NGC also mentions the existence of an overstruck 2 reales 1839/8 MV, but there still exists no record in the Census so we are unable to confirm its existence. |

World Coins Price Guide Ecuador 2 Reales 1839

|

El misterio del 2 REALES 1834/5 GJ Lo que se debe tener presente es que todas las monedas con fechas repisadas tienen algo en común, y es que la fecha repisada normalmente está sobre un huésped de un año anterior al repisado. Sin embargo, esta regla tiene su excepción. |

The mystery of the 2 REALES 1834/5 GJ. What should be borne in mind is that all the coins with overdates have one thing in common, which is that the overstruck date is normally over a date earlier than that of the overstriking. However this rule has an exception. |

2 reales 1834/5 GJ

| En el compendio ECUADORIAN COINS – An Annotated checklist – Edition 2016 por Dale Seppa, en la pág. 18, reporta la existencia de una moneda de 2 Reales con fecha repisada 1834/5 GJ, una moneda cuyo repisado es inusual, debido a que es sobre un año adelantado al repisado impreso y no sobre un año anterior como es lo común. | Seppa’s compendium ECUADORIAN COINS – An Annotated checklist – Edition 2016 on page 18 reports the existence of a 2 Reales coin with overstruck date 1834/5 GJ, a coin whose overstriking is unusual in that the overstriking is on a future date compared to the overstriking rather than an earlier date as is normal. |

Moneda 1834/5 en la que se puede observar claramente debajo del 4 los trazos del número 5

1834/5 coin in which traces of the number 5 can clearly be seen under the 4

| En ese compendio, DALE SEPPA menciona que la moneda está certificada por la NGC como VF DETAILS con Hairlines, el mismo que fue subastado por DFS (Daniel Frank Sedwick) en Mayo del 2013 en un valor superior a los US$800. En la subasta DFS menciona que esta pieza es la única conocida hasta el momento, con un valor estimado entre US$1000 a US$2000. Se puede ver la subasta en el link: | In this compendium SEPPA mentions that the coin is certified by NGC as VF DETAILS with Hairlines, the same as was auctioned by DFS (Daniel Frank Sedwick) in May 2013 at a price in excess of US$800. In the auction DFS mentions that this piece is the only one known up till now, with a value estimated between US1000 and US$2000. The auction can be seen at the link: |

| Seppa también menciona en su compendio, que no tuvo la oportunidad de encontrar los registros y el código de verificación asignado por la NGC, para poder estudiar este inusual repisado y confirmarlo, pero es claro de que se trata de una moneda de 2 reales de 1835GJ repisada con el 4. Esto lo confirmamos fácilmente, porque la única diferencia que existe entre las monedas de 2 reales de 1834 de las de 1835, es el punto al final de la palabra CONSTITUCIÓN (todas las monedas de 1834 tienen un punto al final de la palabra mencionada, mientras que las monedas de 1835 no tienen el punto). La moneda repisada de la subasta DFS (1834/5) no tiene el punto, y así lo indica la descripción de la subasta DFS, lo que claramente confirma que se trata de una moneda 1835 repisado con el 4. | Mr. Seppa also mentions in his compendium that he had not had the opportunity to find the records and the verification code assigned by NGC, to be able to study this unusual overdate and confirm it, but it is clear that it concerns a 2 reales of 1835 GJ overstruck with a 4. This we can easily confirm because the only difference which exists between the 2 reales coins of 1834 and those of 1835 is the period at the end of the word CONSTITUCION (all the 1834 coins have a period at the end of the said word, whilst the 1835 coins do not have the period). The overstruck coin from the DFS auction (1834/5) does not have the period, as is indicated in the description from the DFS auction, which clearly confirms that it is a coin from a die of 1835 overstruck with a 4. |

Monedas de 2 Reales 1834 y 1835 donde se observa la característica principal que difiere a ambas acuñaciones, El PUNTO al final de la palabra CONSTITUCION, que solo lo tiene la acuñacion de 1834

2 Reales coins of 1834 and 1835 where can be seen the principal feature which distinguishes both coinages, the PERIOD at the end of the word CONSTITUCION, which appears only on the 1834 coinage

| La moneda de la subasta DFS llegó a mano de varios coleccionistas ecuatorianos, hasta que llegó a mis manos en marzo del 2017, junto con el soporte blanco del Slab y la etiqueta de certificación de la NGC con la que se había subastado en el 2013, pues habían extraído la moneda de su capsula. El código de verificación que tenía aquella certificación era el 2782907-001. En abril del 2017 envié nuevamente esta moneda a la NGC, para que sea revisada por los especialistas de esa certificadora por segunda vez. El resultado obtenido fue exactamente el mismo que el de la certificación anterior: Una moneda de 2 Reales 1834/5GJ con el grado VF DETAILS, con el mismo defecto de Hairlines. Esta nueva certificación tiene código de verificación 2812314-001 | The coin from the DFS auction passed through the hands of several Ecuadorian collectors until I acquired it in March 2017, together with the white holder for the Slab and the NGC certification label with which it had been auctioned in 2013, since the coin had been removed from its container. The verification code on this certification was 2782907-001. In April 2017 I sent this coin to NGC again, so that it could be reviewed by the certification experts for the second time. The result obtained was exactly the same as the previous certification. 2 reales 1834/5 GJ with the grade VF DETAILS, with the same defect of Hairlines. This new certification has the verification code 2812314-001 |

Moneda Certificada en el 2017 Soporte vacio y con la moneda certificada en el 2013

Coin certified en 2017 Empty holder and with the coin certified in 2013

NGC 2812314-001 NGC 2782907-001

2 Reales 1834/5 GJ - NGC 2812314-001 (2017) 2 Reales 1834/5 GJ - NGC 2782907-001 (2013)

Fotos de las monedas certificadas en la NGC de los años 2017 y 2013 respectivamente, que evidencia a ambas monedas como la misma pieza.

Photographs of the NGC certifications of 2017 and 2013 respectively, which shows that both coins are the same piece.

|

Es decir, 4 años después de la primera certificación, la NGC volvió a validar el mismo repisado del 4 sobre 5, con el mismo grado de calidad y registrando el defecto de Hairlines, sin que se informara a ellos de que se trataba de la misma pieza que se certificó en el 2013. Esto lo podemos confirmar con facilidad, al comparar ambos registros fotográficos de la NGC del 2013 y 2017, donde se observa hasta los mismos Hairlines debajo de la letra R en el anverso (2 rayas debajo de la R). Esto hace que nos hagamos las siguientes preguntas: Cómo sucedió este inusual repisado? Por qué el cuño de 1835 fue corregida con el 4? Primero se contactó a Dale Seppa para que revisara el repisado de la moneda, debido a que él ya había anunciado la existencia del mismo, y no había tenido la oportunidad de conseguir imágenes de la pieza en el 2013 para un análisis más minucioso. Él logró validar que el repisado de la fecha existía, y que a su criterio era genuino y propio de la acuñación original de la moneda. También inspeccionó de este particular el Sr. Michael Anderson llegando a la misma conclusión sobre el inusual repisado. Entonces, cómo se explica lo sucedido. Solo podemos formular algunas hipótesis en base a las investigaciones y afirmaciones efectuadas por los historiadores sobre algunos hechos en los periodos 1834 a 1836: 1.- Debemos tener en consideración que uno de los talladores que elaboraron los cuños en el periodo de 1834 y 1835 era el Sr. Eduardo Coronel, quien según menciona Melvin Hoyos en su obra “La Moneda Ecuatoriana a través de los tiempos” fue despedido como tallador de la Casa de Monedas por irresponsabilidades en sus labores, no se aclara qué trabajos irresponsables hizo el Sr. Coronel como para ser despedido, pero hace que nos cuestionemos si podría ser este uno de los errores irresponsables en sus labores? 2.- Melvin Hoyos también menciona en su obra, que el Sr. Eduardo Coronel fue descubierto con un cuño robado de la casa de amonedación. Según referencia de Historia Numismática de Ecuador Inédito, IZA Terán Carlos, ocurrió en marzo de 1836, y la producción en ese año se ordenó comenzar recién el 14 de Julio, de acuerdo a lo mencionado en la obra de Melvin Hoyos página 110, segunda edición. Todo esto nos permite hacer las siguientes observaciones: a.- Era imposible que el robo del cuño correspondiera a uno elaborado en 1836, debido a que la producción de monedas se ordenó en Julio de 1836 y el Sr. Eduardo Coronel fue descubierto con el cuño robado en marzo de ese mismo año. b.- Que nos permite intuir que el cuño robado debió ser del año 1835 o anterior, que eran los que existían hasta antes de ser descubierto el Sr. Coronel, pero es muy probable que hubiera tomado uno de los más disponibles en el momento, lo que podría ser uno de 1835, para usarlo en sus ilícitas labores entre 1835 y/o 1836 hasta ser descubierto. c.- Por la referencia de Historia Numismática de Ecuador Inédito, IZA Terán Carlos, se menciona que el Sr. Coronel realizaba los trabajos de falsificación en la misma casa de amonedación en donde fue descubierto con un cuño robado en marzo de 1836. d.- A inicios de la República, los falsificadores robaban parte de la plata de las monedas de buena ley, haciendo acuñaciones fraudulentas de baja ley, y así obtener rédito con el metal que obtenían.

Considerando estas observaciones, nos permite plantear algunas hipótesis, como la posibilidad de que el cuño robado probablemente fue del año 1835, y pudo haber sido adulterado la fecha por el Sr. Coronel con la del año anterior (1834/5), con la finalidad de poder incorporar sus piezas de mala ley, realizados en la misma casa de amonedación, muy probablemente desde 1835 a inicios de 1836, tratando de ocultarlas entre las monedas de un año en la que ya existía un numerario completo en circulación; para ello hay que recordar que la acuñación de 1835 comenzó en marzo y duró hasta diciembre, razón por lo que el numerario de 1835 al inicio no debió existir las suficientes piezas como para pasar desapercibido sus monedas ilegales. Otra hipótesis puede ser que lo hizo para evitar los controles de calidad de las piezas acuñadas en 1835, al ser marcadas como 1834 estaría exento del control si la moneda no era parte de la producción vigente en el momento. O también pudo haber corregido el cuño simplemente para no tener en su poder un cuño del año en que se hacía una producción. Pero cualquiera de estas hipótesis estaría sujetas a que la pieza en mención sería una pieza adulterada de la época, acuñada en la misma casa de monedas, y que la pieza debería contener poca o ninguna plata; esto habría sido detectado por la NGC o por las personas que revisaron esta moneda, porque cualquier coleccionista con algo de experiencia podía ver que esta pieza es de buena plata. Por otra parte, también es posible que el cuño corregido pudiera haber golpeado, en buena plata, una o varias piezas después de que este fuera recuperado cuando descubrieron al Sr. Coronel, ya sea para el registro o simplemente por error. 3.- La tercera hipótesis se basa en una simple pregunta: ¿Qué hecho relevante se dio en 1835 que pudo afectar la concepción de las monedas de ese año? El 13 de agosto de 1835 se promulgó la 2da Constitución del Ecuador eliminándose la idea de la confederación con Colombia y se cambia el nombre “Estado del Ecuador en la República de Colombia” (en las monedas se abrevia como “El Ecuador en Colombia”) por “República del Ecuador”. Entonces corresponde averiguar en qué meses se elaboraron los 2 reales de 1835, ya que si todo o parte de los mismos se hicieron luego del 13 de agosto, existe razón para pensar que su año pudo haber sido corregido intencionalmente para que su diseño no contraríe lo que establecía la nueva Constitución. En tal caso sería más fácil corregir el último dígito del año que el nombre de la Nación. Si esta hipótesis fuera cierta, este rarísimo ejemplar evidenciaría la intención de evitar que el monetario producido en 1835 incumpla lo establecido por la Constitución sancionada el 13 de agosto de ese año. Quizás hubo la intención de corregir el año, se probó la viabilidad en unas pocas piezas y al final se resolvió no realizar la corrección quedándonos este ejemplar que se convertiría en un testigo de los cambios políticos y constitucionales del país. Este suceso, del cambio de nombre a República del Ecuador, coincide con el año preciso de elaboración de esta moneda repisada. Probablemente nunca sabremos la real causa de porque se hizo ni cómo, pero lo que sí es seguro es que la pieza cuenta con este inusual detalle, que fue verificado por la NGC en dos ocasiones (en el 2013 y 2017). Además fue revisado por personas con mucha experiencia en monedas coloniales y pre-decimales, como Daniel Frank Sedwic, cuando presentó esta pieza en su casa de subasta en el 2013, calificándola como única conocida hasta el momento, y los señores Dale Seppa y Michael Anderson quienes tuvieron la oportunidad de estudiar este inusual repisado. Definitivamente debe tratarse de una moneda muy poco común. Si algún coleccionista tiene alguna pieza con este tipo de repisado (1834/5), repórtelo (incluir fotos) a This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it. para registrar su existencia. |

That is to say that four years after the first certification NGC again validated the same overdate of 4 over 5, with the same grade of condition and recording the defect of Hairlines, without being informed that it involved the same piece that had been certified in 2013. This we can easily confirm by comparing both NGC photographic records of 2013 and 2017, where can be seen even the same Hairlines below the letter R on the obverse (2 marks below the R). This causes us to ask the following questions: How did this improbable overdate happen? Why was a die of 1835 corrected with a 4? First Mr. Dale Seppa was contacted so that he could review the overstrike, since he had already announced its existence and had not had the opportunity to obtain photographs in 2013 for a more detailed examination. He succeeded in confirming that the overdate existed, and that in his opinion it was genuine and an authentic original mintage of the coin. Mr. Michael Anderson also checked this aspect, arriving at the same conclusion about the improbable overdate. So, how do we explain what happened? We can only offer some hypotheses based on the research and conclusions reached by historians about the events of the period 1834 to 1836: 1. – We must take into account that one of the engravers who prepared dies in the period of 1834 and 1835 was Mr. Eduardo Coronel, who, according to Melvin Hoyos in his “La Moneda Ecuatoriana a través de los tiempos”, was dismissed as mint engraver for irresponsibility in his duties. It is not explained what irresponsible duties Mr. Coronel committed to be dismissed, but we must wonder if this could have been one of the irresponsible errors in his duties. 2. – Melvin Hoyos also mentions in his work that Mr. Eduardo Coronel was found with a die stolen from the mint. This, according to the unpublished Numismatic History of Ecuador of IZA Terán Carlos, occurred in March 1836, and production in this year was ordered to begin only on 14 June, according to what is said in Melvin Hoyos’ book, second edition, page 110. All this allows us to make the following observations: a.- It is impossible that the theft of the die related to one produced in 1836, since the minting of coins was ordered in June 1836 and Mr. Eduardo Coronel was found with the stolen die in March of that year.. b.- We can infer that the stolen die must have been of the year 1835 or earlier, which were those which existed before Mr. Coronel was found out, but it is very probable that he would have taken one of those most readily available at the time, which would have to be one of 1835, to be used in his criminal activity in 1835 and/or 1836 until being found out. c.- According to the unpublished Numismatic History of Ecuador of IZA Terán Carlos, it is said that Mr. Coronel carried out his forgeries in the same mint where he was found with a stolen die in March 1836.. d.- In the early days of the Republic, forgers used to steal part of the silver from coins of good fineness, making fraudulent coinages of base fineness, and thus making a profit from the metal they obtained.

Considering these observations, we can develop certain hypotheses, such as the possibility that the stolen die was probably of the year 1835, and the date could have been altered by Mr. Coronel to that of the previous year (1834/5) with the objective of being able to incorporate his base pieces, produced in the same mint, very probably from 1835 to early 1836, trying to hide them among coins of a year of which there already existed a complete supply in circulation; for which it is necessary to remember that the 1835 mintage began in March and lasted until December, so that at the beginning not enough of the 1835 coinage could have existed to conceal the false coins. Another hypothesis could be that he did it to avoid the quality controls of coins minted in 1835, being dated as 1834 they would be exempt from control if the coinage was not part of the production current at the time. Or he could have changed the die simply so as not to have in his possession a die of a year currently in production. But any of these hypotheses would require that the piece under consideration would be an adulterated coin of the time, coined in the mint itself, and that the piece would have to contain little or almost no silver. This would have been detected by NGC or by any of the persons who reviewed this coin; furthermore collectors with any experience could see that the coin is of good silver. Alternatively the mint could have struck this piece in good silver after the die was recovered from Mr. Coronel, either for the record or simply by mistake. 3.- The third hypothesis is based on a simple question: What relevant fact occurred in 1835 which could affect the design of that tears coins? On 13 August 1835 the second Ecuadorian Constitution was promulgated, abolishing the idea of the confederation with Colombia and changing the name “State of Ecuador in the Republic of Colombia” (abbreviated on the coins as “El Ecuador en Colombia”) to “República del Ecuador”). Therefore it is necessary to ascertain in which months the 1835 2 reales were produced, since if all or part of them were made after 13 August there is reason to think that the date could have been corrected intentionally so that the design did not contradict what had been established by the new Constitution. In such a case it would be easier to correct the date than the name of the country. If this hypothesis were correct, this extremely rare specimen would indicate the intention to avoid the 1835 coinage being inconsistent with what had been approved by the Constitution on 13 August of that year. Perhaps having had the intention of correcting the date, they tested the viability of a few specimens and in the end decided not to make the correction, leaving us this example which would become a witness to the political and constitutional changes in the country. This event, the change of name to República del Ecuador, coincides with the exact year of the manufacture of this overstruck coin. Probably we shall never know the real reason why and how it was done, but what is certain is that the piece has this unusual detail, which was verified by NGC on two occasions (in 2013 and 2017). Furthermore it was reviewed by persons with much experience of colonial and pre-decimal coins, such as Daniel Frank Sedwick, when he offered this piece in his auction house in 2013, describing it as the only one known up to that time, and Messrs. Dale Seppa and Michael Anderson, who had the opportunity to study this improbable overstrike. Definitely it must be a very scarce coin. If any collector has a specimen with this type of overstrike (1834/5), report it (with photographs) to This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.to record its existence and be considered in future article. |